Stem Cell Therapy for Diabetes: Progress and Challenges

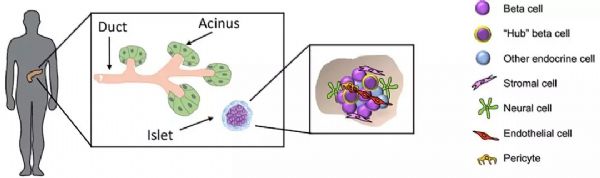

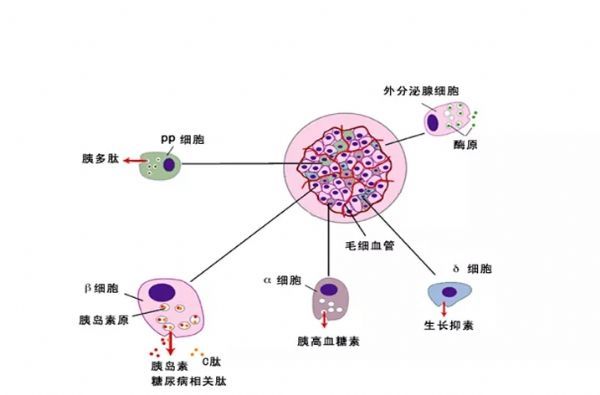

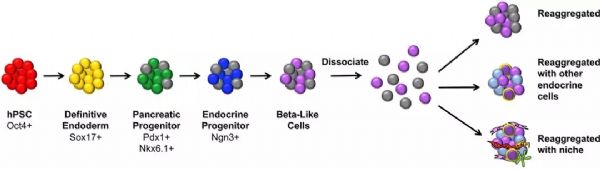

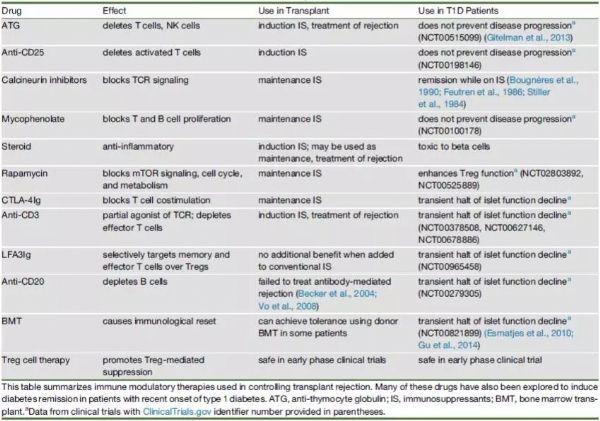

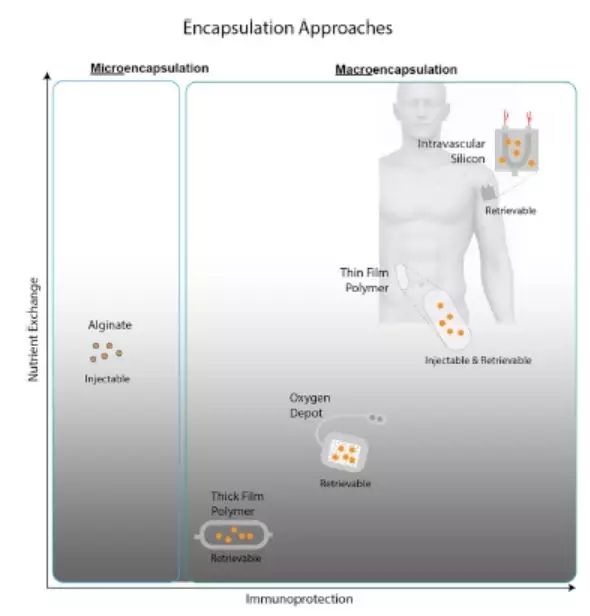

Stem Cell Therapy for Diabetes: Progress and Challenges August 15, 2018 Source: Stem cells say A century ago, type 1 diabetes meant the death penalty. Now, it's just a daily illness. The well-known international journal Cell Stem Cell publishes a review that outlines the key technologies and core issues of stem cell therapy for diabetes. The article looks at how to generate functionally intact islets, immune problems in islet cell transplantation, and future directions and strategies for stem cell microencapsulation. It is a good article worth learning. Stem cells and diabetes Advances in recombinant insulin synthesis and drug delivery have fundamentally reduced the incidence and mortality of diabetes-related diseases for nearly a century. Despite this, there are still 400 million patients worldwide suffering from fatal effects such as diabetic nephropathy, eye disease and nervous system diseases. Strict diet control can slow or prevent the development of complications of type I and type II diabetes. Unfortunately, this strict diet control can also cause hypolipidemia, so the implementation of the measures is also limited by the patient's condition. By replacing the beta cells with solid pancreatic organ transplantation or islet transplantation, it is possible to achieve good control without using insulin. Due to the limited source of islet tissue, the use of stem cells to produce sufficient insulin-secreting cell resources will satisfy the broad needs of beta cell replacement and insulin-independent. The development of stem cell technology, the advancement of tissue engineering and the development of biological materials have made it closer to clinical transformation and become the most potential alternative treatment strategy for diabetes. However, the key technologies and core issues of stem cell therapy for diabetes remain to be further studied and overcome. How to generate fully functional islets In the past ten years, significant progress has been made in the production of functional beta cells using human stem cells. The basic strategy is to recapitulate the main pathways of pluripotent stem cell differentiation during embryonic phase: the formation of definitive endoderm, then pancreatic endoderm, then to endocrine precursor cells (progenitor cells) and ultimately to islet cells. Recent research has focused on the production of individual cells that respond to glucose stimulation and secrete insulin. Several laboratories focus on producing fully functional beta cells and islet cells, and soon can replace human islets as a source of insulin-secreting cells. Figure-1 The pancreas is composed of exocrine and endocrine regions. The latter consists of small ball-like micro-organs called Inset. Each islet contains insulin-secreting beta cells, as well as other hormone-secreting endocrine cells (α, δ, epsilon, and PP cells). The so-called "central" cells are a subset of beta cells that coordinate islet cells to synergistically release insulin after glucose stimulation. Endocrine cells are not isolated, but exist in niches of various cell components: stromal cells, nerve cells, endothelial cells, and perivascular cells. Although significant progress has been made in the preparation of insulin-secreting cells from human embryonic stem cells, the process of cell formation that perfectly replicates all the characteristics of endogenous beta islet cells and achieves all of their functions remains to be elucidated. Considering that the beta islet cells in the body are not independent, but in an intricate 3D pancreas environment, the preparation of "intact" islet cells should contribute to pancreatic function reconstruction. In fact, the maintenance of beta cell function is highly dependent on the complex cellular structure of islets, whereas isolated islet cells behave differently from islet cells in intact structures. For example, due to the decrease in basal insulin secretion and maximum insulin secretion under glucose stimulation, isolated beta cells have a lower insulin secretion function under glucose stimulation than cells in intact structural state. In addition, other mechanisms, such as the coordination of cell-cell signaling, and the cell gap junction protein Connexin-36, play an important role in maintaining insulin levels and synchronizing with β-cells and islets. Considering the optimal treatment of human embryonic stem cells for the treatment of diabetes, it is necessary to consider how to reconstruct the contact between islet cells and cells and the structure of islet-to-microenvironment communication when preparing cells. Another dominant function of beta cells is the exchange of information with other cells in islet niches, including a variety of non-endocrine cells such as endothelial cells, pericytes, nerve cells, and mesenchymal cells. In particular, the blood vessels of the islets in the pancreas are highly developed, and each beta cell may have one or more contacts with endothelial cells and form a special ultrastructure at the contact. During pancreas development, endothelial cells are initially recruited by VEGF-A secreted by endocrine cells to rapidly growing islets. This is followed by endothelial cell synthesis and secretion of the islet membrane matrix and serves as a key regulator of beta cell growth, survival and function. Otonkoski team studies have shown that human islets contain two basement membranes around endothelial cells and beta cells. In view of the special relationship between beta cells and supporting cells in the natural environment, remodeling of certain elements in endogenous beta cell niches in vitro may promote the survival and function of hESC-derived beta cells. Islet vascular niche includes not only endothelial cells, but also parietal cells, called pericytes. Pericytes are wrapped around the endothelial cell to provide structural support and to produce mature functional blood vessels and to regulate endothelial cell proliferation, survival and function. The role of pericytes in normal islet function is not fully understood, and genetic knockout studies indicate that loss of pericytes in adult rat islets leads to impaired insulin expression and glucose clearance. Given the importance of islet cell structure for endocrine function, culture systems can be designed to reproduce the elements of the complex three-dimensional structure of islets during development. Various methods are used to produce engineered islets in vitro, or so-called 'false islets'. A number of studies have shown that both in vitro and in vivo, after the transplantation of the re-aggregate of the pseudo-islets, the function has been improved. There is also evidence that GSIS (glucose-stimulated insulin secretion) is improved when beta cells re-aggregate with endothelial progenitor cells compared to pseudoislets consisting only of beta cells. Figure-2 Production of beta-like cells with human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) involves the promotion of pluripotent stem cells through a series of intermediate progenitor cells. Upon completion of the directed differentiation, the β-like cell clusters can be dissociated and re-aggregated into a cluster of islet-like cells of a determined size and composition. Reaggregation with other types of endocrine cells (which themselves may be derived from hPSCs) may improve glucose homeostasis, possibly through the differentiation of certain hPSC-derived beta cells into central cells. Finally, endocrine cells can re-aggregate with niche cells, more closely recreating the interaction of local microenvironments that are critical for beta cell function. In summary, more work needs to be done to determine the cell composition and structural layout that best fits human islet function. Possible challenges include determining how to obtain the desired seed cells in a human islet niche, especially considering that certain cell types lack true specific markers and have limited sources. One option is to generate these cells from hESCs or induced pluripotent stem cells (ipsCs). Another challenge is that the current technology for creating artificial islets relies on the self-organizing properties between endocrine and non-endocrine cells. Perhaps one day, 3D printing of islet tissue may be possible to complete the desired structure. Immune problems in islet cell therapy The recent success of using beta cell replacement to treat T1D, coupled with the production of hESC- or ipsC-derived beta cells, provides a roadmap for effective treatment of the disease. However, immune system problems remain a major obstacle to the widespread adoption of cell replacement therapy for patients with T1D and some T2D. Current immunosuppressive agents are effective, but require lifelong treatment and, in many cases, side effects and toxicity, so most of these treatment strategies are still limited to very severe cases. 1) First of all, the problem of immune rejection. In T1D patients, transplanted allogeneic beta cells are subject to alleged immune-mediated rejection, and if not inhibited, the transplanted cells can be cleared within a few days. T cells are a major factor in alloimmunization, and their activation is due to the T cell receptor (TCR) recognizing the antigenic peptides bound by major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs). High polymorphisms in MHC proteins (known in humans as human leukocyte antigen HLAs) are major targets for allogeneic immune challenge, secondary to histocompatibility antigens, such as male antigens or mitochondrial antigens found in female receptors, despite Slower speed can also cause rejection. Although immunosuppression protects grafts from rejection, extensive immunosuppression compromises the patient's immune system, making them vulnerable to infections and malignancies. An ideal strategy is to train the immune system to accept transplanted cells and avoid chronic systemic immunosuppression. Many preclinical animal models have achieved immune tolerance to transplanted tissues and are currently developing potential tolerable therapies for humans. In the past 20 years, people have been working together to study strategies for inducing transplant tolerance, one of which is to construct a donor-receptor hematopoietic chimera. In the presence of donor immune cells, the cultured recipient immune cells receive donor-derived cells as their own cells, thereby preventing transplant rejection. One challenge with this approach is the instability of the mixed chimeric state, leading to an imbalance in the host or donor immune system that is dominated by one side and takes over. When donor cells predominate, the risk of graft-versus-host disease is high; when recipient cells predominate, tolerance to donors is often lost. Another strategy is to promote the function of Tregs with adoptive cell therapy. One challenge with adoptive Treg therapy is that a large number of effector T cells that respond to the donor can overwhelm Treg-mediated inhibition. The use of Tregs to control rejection requires the reduction of T cells in the recipient that respond to the donor. There are continuing new preclinical results suggesting that Treg cell therapy can stabilize hematopoietic chimeras, so both therapies may work synergistically to achieve more reliable and long-lasting tolerance. 2) Second is the problem of autoimmunity. In T1D patients, islet autoantigen-specific T cells can also attack and destroy transplanted beta cells, thereby promoting the rejection of transplanted beta cells. Strategies for controlling autoimmune recurrence in T1D patients and rejecting transplanted beta cells can be taken to study the measures used in controlling autoimmunity in T1D patients. Extensive research efforts have been made to restore self-immune tolerance in T1D patients. Interestingly, many immunosuppressive drugs commonly used to prevent transplant rejection do not effectively induce the relief of diabetes. However, most immunosuppressive drugs commonly used to prevent allograft-mediated transplant rejection can cause short-term diabetes relief, but there is no long-term efficacy. In immunosuppressed pancreatic and renal transplant recipients, traditional drugs are used to suppress autoimmune responses, and autoimmune relapses that attack islet cells are also observed. Targeted therapy with T cells and B cells, such as anti-CD3, Abatacept (similar to the CTLA-4Ig molecule described above) and anti-CD-20, can temporarily stop the beta cell function of some new T1D patients. Antithymocyte globulin is a drug commonly used to induce T cell failure in organ transplantation. It does not prevent beta cell loss at high doses. Low doses have a short-term benefit when used in combination with G-CSF. In contrast, another T cell targeting agent, LFA-3Ig (Alefacept), stabilizes beta cell mass in patients with new-onset disease. Common to anti-CD3, Abatacept and alefacept is that they are relatively selective for effector T cells while retaining or even enhancing Tregs. Therefore, their therapeutic effect may be due to the ability to promote Treg function while blocking effector T cells. These tips for controlling the effects of islet autoimmune attacks provide guidance for designing more effective combination therapies to induce long-term tolerance. Table-1 Immunomodulatory drugs for alloimmunization and autoimmune responses. In addition to the extensive immunomodulatory strategies described above, there are also ongoing efforts to develop islet antigen-specific therapeutic approaches. Preclinical data suggest that peptide vaccines or nanoparticles prepared with islet major antigens can target specific effector cells to induce immune tolerance, but the effectiveness of these strategies in patients remains to be demonstrated in clinical trials. Although many of these studies have shown some effects in a small patient population, and several projects are undergoing new antigen therapy attempts, determining the precise antigen, time, and method of administration is critical to maximize And effectively test the efficacy. The challenge for antigen-specific immunotherapy is the number of islet antigens that the immune system targets; only killing the killing function against one or a group of islet antigen-specific T cells is not sufficient to alter the progression of the disease. In addition, the specificity of islet antigens may be different in different patients and different disease stages, so it is difficult to know which specific islet antigens are targets. Methods that induce primary antigen-specific immune regulation may be more effective and easier to apply to different patient populations. Treg cell therapy offers a number of attractive features that are related to the regulation of the major antigen-specific responses by effector T cells. For example, Tregs control unwanted immune responses through 'association inhibition' and 'infectious tolerance'. In associated inhibition, Tregs activated by one antigen can inhibit responses to other antigens that occur in the same tissue microenvironment. In infectious tolerance, Tregs create a tolerant tissue microenvironment that allows other nearby activated T cells to adopt regulation rather than effect fate. This allows the inhibition of Tregs to spread over time, not just the presence of the starting cells. These characteristics ensure that Tregs with limited specificity are capable of specific, significant and long-lasting control of local other immune cells. Indeed, a single injection of islet antigen-specific Tregs induces a lifetime of remission in diabetic autoimmune non-obese diabetic mice. Early trials of Treg cells in patients with T1D are currently underway, demonstrating the feasibility and safety of this approach in patients. Future direction and strategy of stem cell microencapsulation It is an indisputable fact that stem cells can improve and treat many diseases. In the previous section, the production of stem cell-derived islet cells and the immune disorders faced were introduced, but the actual progress and challenges are more troublesome. For example, clinically, islet transplantation technology is becoming more and more mature. Research on transplantation location and blood supply makes islet transplantation a gold standard for treatment; patients' health status needs to be considered to ensure satisfactory clinical treatment. Efficacy. As the beta cells produced by stem cells are getting closer to the characteristics of endogenous cells, the clinical application is becoming more and more reliable. However, the difficulty of immune rejection is still not to be underestimated. Gene editing methods to eliminate immune-related genes to reduce immune rejection or improve immune tolerance, but due to the complex, interrelated and constrained relationship of cells, it is easy to cause imbalance of the immune system, still need deep and careful consideration and choice. Tissue engineering methods are used to encapsulate insulin-secreting cells into microcapsule devices of special materials, which can provide insulin-secreting cells on the one hand and immune cell attack on the other. Although the actual operation process, it also faces many complicated problems, especially the problems of technical realization means, but there are still clinical experimental products. Therefore, the outlook is still optimistic. Stem cell microencapsulation has entered the clinical trial phase. In 2014, the first clinical trial based on ESC treatment of type 1 diabetes products (NCT02239354), named VC? 01 (ViaCyt), a hESC-derived pancreatic endoderm cell (referred to as PEC?01 cells), is a subcutaneous injection implanted semi- osmotic drug delivery device that is immunoisolated to allow oxygen and nutrients to pass through. This is an open phase 1/2 clinical trial evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the diabetes treatment candidate PEC-Encap. There is another clinical trial (NCT01652911), which is not immunoisolated, implanted in the lower blood vessels for 30 days, and then implanted with islet cells. The three-year clinical trial was terminated after recruiting three patients. In general, the rapid progress of related disciplines provides a new and desirable treatment for the treatment of diabetic patients. Although there are still many technical obstacles in these areas, the new capsule technology, new immunomodulation methods, improvement of stem cell differentiation methods and the combination of genetic editing methods will bring revolutionary T1D and T2D patients. Modern cell therapy methods. Fingerprint Safe,Biometric Fingerprint Safe,Portable Fingerprint Safe,Fingerprint Lock Safe Box Ningbo Reliance Security Technology CO.,Ltd , https://www.reliancesafes.com